The Abduction and Rescue of Kaomi

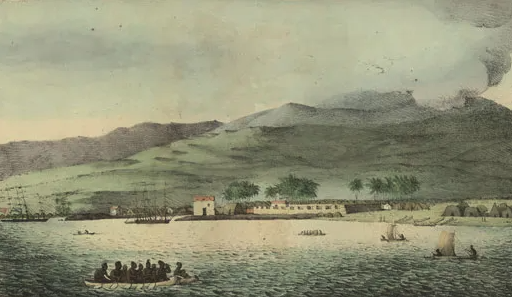

Honolulu Fort, located on the harbor of the area known by Hawaiians as Kou, was the earliest Western-style fort constructed in the islands. It was also the site of a pivotal moment in the turbulent transition between KānakaʻŌiwi and Western ways of governance and religion: the abduction and rescue of Kamehameha III’s intimate same-sex friend and co-ruler of Oʻahu, Kaomi. In the early 1800s, Kamehameha I granted permission for Russian traders who had come to the island to build a storehouse. When he found out they were actually building a military fort, he had the governor of Oʻahu remove the foreigners and expand the structure. By 1830, there were forty guns mounted on the parapets, leading to the nicknames Kekuanohu, which literally means“the back of the scorpion fish,” and Kepapu, or “the gun wall.”

This was a tumultuous period in Hawaiian history. When Kaʻahumanu, the kahunanui or regent of the kingdom, died unexpectedly in 1832, the eighteen-year-old Kamehameha III began to rebel against the Christian laws and edicts Kaʻahumanu had established under instruction by Protestant missionaries. Kamehameha III’s main political supporter was Kaomi Moe, an intelligent and highly educated individual known for both his humor and healing skills. He was also the son of a Tahitian father and Hawaiian mother. Kamehameha III and Kaomi had been living together for several years, and in time became aikāne, or intimate friends of the same sex—a relationship that was well known and publicly acknowledged even by the missionaries.

Kamehameha III elevated Kaomi to the title of “moi kuʻi, aupuni kuʻi,” or joint king, joint ruler, and gave him the right to distribute land, clothing, and money and draw upon the kingdomʻs budget (Samuel Kamakau, Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi, p 335). Historian Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp notes that ku'i in Hawaiian is a very strong word that implies a union or marriage.

Early in March 1833, a crier was sent through the streets of Honolulu to proclaim the abrogation of all laws except theft and murder. Soon hula and mele were being performed again, rum and ʻawa were freely made and distributed, gambling was permitted, and people were free to have sex with whomever, and however, they pleased, sometimes in groups. Hawaiians from all over the islands flocked to Oʻahu, but the missionary establishment and Christian aliʻi were horrified. The “time of Kaomi” didn’t last long. According to a detailed account written by Kamakau in Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi, some of the Christian chiefs hatched a plot to assassinate Kaomi, and sent an aliʻi named Kaikioʻewa to his house in what is now downtown Honolulu. Despite the fact that Kamehameha III had surrounded the house with guards, and proclaimed that no one was to enter the compound at pain of death, Kaomi allowed himself to be bound with ropes and dragged to Honolulu Fort, proclaiming that “ua ae aku e paa i ke kaula, a e make paha, e make no” (If death is my prophecy, death it shall be). According to Kamakou (p338), the excecution was prevented only by the physical intervention of Kamehameha III:

At this moment the king hurried in, dressed in the scant clothing he was wearing when a guard had run to inform him that, "Kaomi is being killed by Kaikioʻewa." The king himself untied Kaomi's bonds. Kaikioʻewa sprang forward and grappled with the king, over and under they fought until the king held Kaikioʻewa fast. Then words poured from Kaikio’ewa's mouth declaring, "You are not the ruler over the kingdom if you keep on indulging yourself in evil ways!" but the king did not answer him. Kaomi was released and went back with the king to Kahaleuluhe, and the king's place was made tabu.

Although Kaomi survived, he soon thereafter removed himself from the court, perhaps in an effort to preserve the power of the king. Ka Wā Iā Kaomi was over, and in the interest of maintaining the Kingdom's independence, Kamehameha III increasingly integrated both Christian and Western legal values into the Island’s governance.

The fort remained on the harbor, at what is now the intersection of Queen and Fort Streets, and was the administrative center of the kingdom as well as the site of brief conflicts with the English and French navies.

In 1857, with the harbor full of whaling and trading vessels, it was no longer needed for defense and was torn down. Many of its coral blocks were used to extend the shoreline out into the harbor and to pave city sidewalks.

Story by Dean Hamer for Lei Pua ‘Ala Queer Histories of Hawai’i.

Image credits:

Vue du port hanarourou (View of the port of Honolulu), 1816. Louis Choris, artist. Published in Voyage Pittoresque du Autour du Monde, Paris, 1822. Public Domain in Wikimedia Commons.

View of Honolulu Fort, interior, Public Domain photo in Wikimedia Commons of Hawaii Historical Society painting by Paul Emmert c. 1853.

Portrait of King Kamehameha III of Hawaii in Military Uniform 1842 by Alfred Thomas Agate from Charles Wilkes narrative of the U.S. Exploring Expedition. Public Domain in Wikimedia Commons, source - Smithsonian Institution National Anthropological Archives NAA INV 08527400 OPPS NEG 90-10,261.

Photos of Walker Park, the site of Honolulu Fort, by Dean Hamer.

Additional Reading:

Ruling Chiefs of Hawaiʻi (revised Edition) - Samuel M. Kamakau - The Kamehameha Schools Press, 1992

Ka Moolelo Hawaii: No Ka Noho Alii Ana Kauikeaouli Maluna O Ke Aupuni A Ua Kapala O Kamehameha III - Samuel M Kamakou - Ke Au Akoa, Vol IV, Number 28, 7 January 1869

Native Land and Foreign Desires: Pehea Lā E Pono Ai? How Shall We Live in Harmony? - Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, 1992

Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism - Dr. Noenoe K. Silva - Duke University Press, 2004

Māhū Resistance: Challenging Colonial Structures of Power and Gender - Adam Keawe Manalo-Camp - Medium, 8/8/20

Mai Poina: Lost to History - Dr. Noenoe K. Silva - The Umiverse - 10/21/20

Mana Lāhui Kānaka - Kamanaʻopono M. Crabbe with Kealoha Fox and Holly Kilinahe Coleman - Office of Hawaiian Affairs, 2017

Living True Aloha (Using the core value of aloha as a weapon against others is pure cultural hypocrisy.) - kuualoha hoomanawanui - The Hawaiian Independent, 10/30/13