BAEHR V. LEWIN

THE LAWSUIT THAT LAUNCHED A MOVEMENT

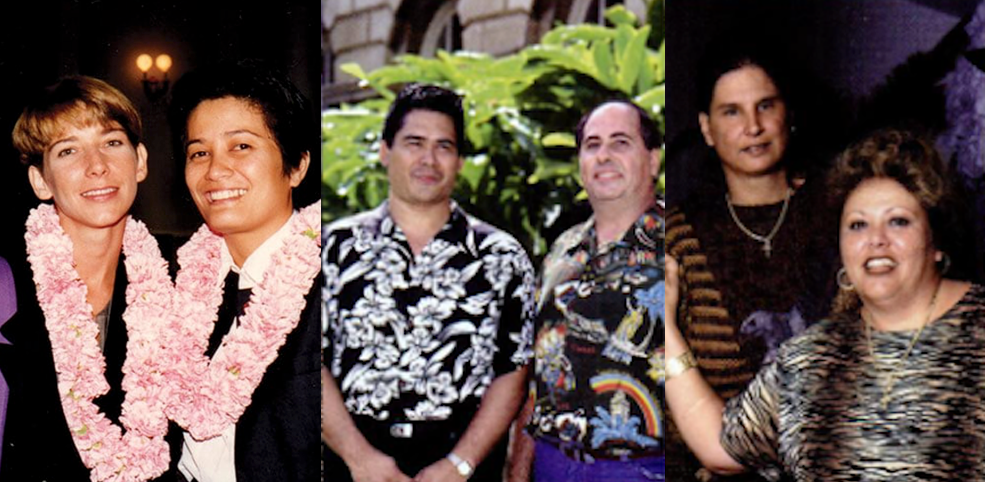

On May 1, 1991, a messenger delivered a five-page document to the First Circuit Court of Hawaiʻi at 777 Punchbowl Street in Honolulu. It was a lawsuit against John C. Lewin, Director of the Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, presented by private attorney Daniel Foley on behalf of three same-sex couples: Ninia Baehr and Genora Dancel, Tammy Rodrigues and Antoinette Pregril, and Pat Lagon and Joseph Melillo. They wanted to get married, but the State of Hawaiʻi wouldn’t let them.

The case started the previous year when Baehr got an ear infection but had no health insurance to cover a doctor’s visit. She called Bill Woods, founder of the Hawaiʻi Gay Community Center, to ask if there was any way for her be added to her partnerʻs health plan. He told her that she could not, but urged her to join a lawsuit to challenge Hawaiʻi’s prohibition on same-sex marriages.

In December, the three couples walked from the Gay Community Center at the Blaisdell Hotel to the State Health Department to apply for their marriage licenses, which were promptly denied. They then walked back to the Blaisdell, where the office of the local ACLU was also located, to ask for legal assistance, but the organization declined to take the case, as later did the national Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund..

Fortunately, young civil rights attorney Dan Foley (pictured at right) was willing to take a shot. A former Peace Corps volunteer in the Kingdom of Lesotho, practicing Buddhist, and past legal director for the Hawaiʻi ACLU, he was one of – if not the only – lawyer in Hawaiʻi with experience representing LGBTQ+ issues. His best-known case was to overturn a ban on a “Miss Gay Molokai Pageant,” a hula school’s fundraiser that was opposed by the local mayor and evangelical churches in 1985.

When Foley accepted the same-sex marriage case in March 1991, he faced a difficult landscape. Most Americans considered homosexuality to be morally wrong, gay men were being blamed for the AIDS crisis, and the United States Supreme Court, after ten years of appointments by Republican presidents, had turned sharply rightwards and was especially hostile to sexual minorities; according to the court’s 1986 decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, same-sex couples didn’t even have a right to have sex, much less form a family.

But Foley wasn’t in the continental USA. He was in Hawaiʻi -- one of the most progressive states in the country, with strong laws protecting gender equality and civil rights, and a cultural history of not only accepting but honoring same-sex relationships. So he decided on a legal strategy that would rely solely on the Hawaiʻi State constitution, with no reference to federal rights. Then, knowing that the existing law in Hawaiʻi clearly did not allow for same-sex marriages, he wrote an unusually concise complaint aimed at bringing the case as quickly as possible to the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court rather than getting bogged down over the detailed facts of the case.

At the heart of Baehr v. Lewin was the fact that the three couples had been denied marriage licenses “solely on the ground that the plaintiffs are of the same sex.” This, said Foley, was a violation of equal protection under the law according to the Hawaiʻi State Constitution, which guarantees that “no person shall be discriminated against because of their race, religion, sex or ancestry.” The emphasis on sex was a smart strategy given Hawaiʻi’s long support for women’s rights. Once a largely matrilineal society, Hawaiʻi was the first state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment and to add its protections to the state constitution. Hawaiʻi was also home to Congresswoman Patsy Mink, the principal author and driving force behind the Equal Opportunity in Education Act, Title IX, which went on to become a bulwark of LGBTQ+ legal protections.

The second plank in Beahr v. Lewin was privacy. Hawaiʻi is one of only five states that explicitly protects privacy, a right that had been used nationally to allow contraception and abortion even though it is not specified by name in the United States constitution. It was logical to think of marriage as equally private behavior, although in the end the prior Bowers v. Hardwick decision made this argument unlikely to succeed even in progressive Hawai’i.

The lawsuit got its first hearing, in the First Circuit courtroom at Ka’ahumanu Hale, four months later. It didn’t take long – just a week – for judge Robert Klein to find against the plaintiffs, dismissing the case and justifying the existing law as something that was needed to “advance the general welfare of the community.” But in what might be viewed as a confirmation of the logic and power of Foley’s equal protection argument, the judge found it necessary to supplement his decision with the claim that gays and lesbians did not qualify as a protected class because their sexuality is “not immutable,” and that “citizens cannot expect government’s policies to support their lifestyles or personal choices.”

It was a bizarre claim to make in regard to a lawsuit where this issue played no role, following a hearing where no evidence was introduced. But speaking personally, as a scientist who studied the relationship between genetics and sexual orientation for many years, I can say that it is exactly the sort of self-righteous rhetoric that is all too often trotted out in support of anti-LGBTQ+ discriminatory laws and practices. The one good thing that can be said about Klein’s decision is that it was so poorly written that it was likely to be overturned on appeal.

When the case did indeed arrive at the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court, another key advantage of Foley’s strategy became evident. Because the case was based solely on Hawaiʻi law, it could never end up at the United States Supreme Court, meaning that the court’s ruling would not be overturned elsewhere. Judges, like most people, prefer their decisions to be respected. Now, as jurists in a progressive state with a strongly Democratic population, they had an opportunity to interpret the law in a way that would have profound and long-lasting impact – not just on marriage but on the visibility, inclusion, and dignity of a long-oppressed minority group.

On May 5, 1993, the Supreme Court of Hawaiʻi announced its decision in favor of the plaintiffs. It was the first time any court had recognized a fundamental right to marriage for queer people. There was still a long and winding road ahead, but as Foley commented to Woods, “Our case is more than a gay rights case. It is a human rights case.”

Story by Dean Hamer. Mahalo nui to Dan Foley for thoughtful discussion.

Top photo: left to right: Ninia Baehr & Genora Dancel, Pat Lagon & Joseph Melillo, and Antoinette Pregil & Tammy Rodrigues.The Advocate. Photo of Dan Foley: Hawai’i New Now. Newspaper clip: Star-Bulletin, May 2, 1991